As admired in the exhibit, Souls Grown Deep, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Gee’s Bend is a small, poor, black community in Alabama. It’s only 44 miles west of Selma — where in 1965 Martin Luther King, Jr. led protest marches to Montgomery, Alabama. But surrounded on three sides by the Alabama River, Gees Bend is isolated, a far cry from modern-day consumerism and attitudes. Most of the 700+ folks who live there are descended from slaves. After the departure of Joseph Gee and the dispersal of his slaves, the Pettway family ran the plantation. In order to stay on this land, many of them had to take on the Pettway surname. Sharecroppers and tenant farmers kept workers in poverty. Planting and picking cotton, peas, and peanuts, and tending hogs and cows provided long, hard days of bare subsistence farming. But poor by any standards, generations of Gees Bend women have created a rich legacy of quilt masterpieces. And these have garnered attention and accolades from the art world.

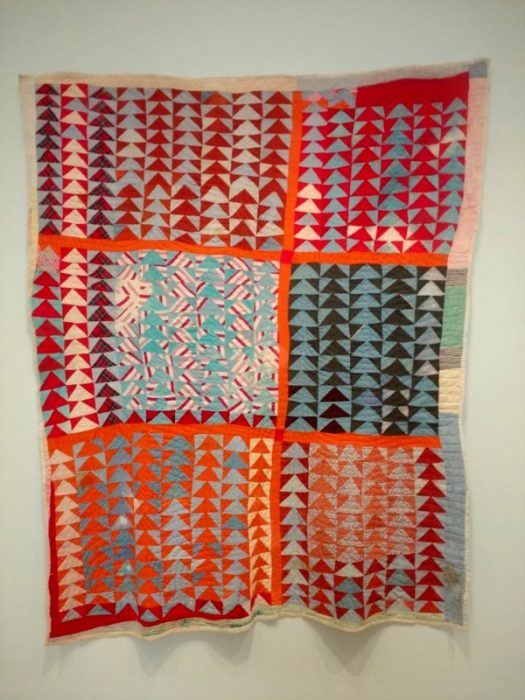

Now, when I worked on needlework and craft magazines in NYC in the 1980s, I studied pictures of American quilts made by European descendants, in order to write directions for recreating them. Typically, these quilts featured hundreds of patches — like the quilt at the top of this post, but each patch absolutely identical. Precise and ultra-fine handiwork, heirloom patterns, fabrics from England and France. Such fancy-work could only be made by women living in the lap of luxury, with plenty of time and money. Even the country quilts were mostly made using fabrics off the bolt rather than scraps and repurposed clothing.

So I admit, it took me a while to appreciate the wonky, asymmetrical compositions with edges out-of-square of the Gees Bend quilts. These women received only a few weeks of education a year — squeezed in after planting and again after the harvest. Quiltmaking, too, was fit in only after work and chores were seen to. They used what they had: denim and wool work clothing too far gone to mend, feedsack bags, and corduroy remnants when Sears was paying for pillow-making. Especially admirable in an age when reusing, recycling, and repurposing has gained moral importance. Yet these quilts, meant for the beds where sleeping family members needed warmth, now grace the same museum walls that show minimalist abstract art by Josef Albers, Piet Mondrian, Paul Klee, Mark Rothko, Richard Diebenkorn, and Sean Scully.

From an interview with Loretta Pettway: “I didn’t like to sew. Didn’t want to do it. I had a handicapped brother and I had to struggle. I had a lot of work to do. Feed hogs, work in the field, take care of my handicapped brother. Had to go to the field. Had to walk about fifty miles in the field every day. Get home too tired to do no sewing. My grandmama, Prissy Pettway, told me, ‘You better make quilts. You going to need them.’ I said, ‘I ain’t going to need no quilts.’ But when I got me a house, a raggly old house, then I needed them to keep warm. We only had heat in the living room, and when you go out of that room you need cover. I had to get up about four, five o’clock, and get coal. Make a fire. Them quilts done keep you warm.”

Like all the women in the show–and for that matter, in Gees Bend, Irene Williams has lots of quiltmaking relatives and neighbors. However this particular woman seems to have stitched to her own aesthetic. Since the age of 17, quiltmaking has been for her a solitary activity, a relief from working the cotton fields and raising six children. She explains, “When I got married, I started making quilts. I just put stuff together.” Among that “stuff” were basketball jerseys she pieced into a quilt top. Art critics delight in the whimsical way this work recalls maps with housing plots and numbers — or reflects a sly sense of humor.

Irene Williams also created the piece below. Here, too, she used what she had, which obviously included a good deal of polyester knit. Using such a fabric means you get lots of stretching — distorted seams, puffy texture, and wavy edges. But you also get intense color, an iconoclastic shape, and a bold, attention-grabbing graphic that made this the image used to represent the entire Souls Grown Deep exhibit for the Philadelphia Museum of Art promotional materials.

I recently led a group on an informal tour through the exhibit, sharing what I knew and listening to their reactions. Each person chose her favorite, and this one was selected by several. My charges also asked how fame had affected their lives. This article explains it best. Many of the quilts originally sold for $75 when the maker thought that was far too much. Or, later, for hundreds of dollars when the value was listed in the thousands. Some quiltmakers cite the satisfactions of recognition and newly installed indoor plumbing, the occasional air conditioner or heater. The Souls Grown Deep Foundation engaged the Artists’ Rights Society to secure for each maker her due: intellectual property rights; copyright fees that are owed for use of the images, remuneration for the work of deceased artists finding it’s way to the rightful next-of-kin. Some of the Gees Benders are grateful, others have engaged in long, drawn out lawsuits in which money is consumed by the plaintiff’s lawyers.

Quilts have put Gees Bend on the map. But it is still a small, poor community.

Everyday that we view art and talk about what we feel and see is and enriching experience. Since I am not a quilter it is enlightening to hear those who quilt focus on the stitching as well as the materials and the color.

It is also enlightening to get your perspectives. You may not be a quilter, Deanne, but you are a social justice warrior and fabric lover with a long history of involvement with textile production and cultural variations showcased in cloth!

Thanks for posting this, and showing us your favorites. I don’t think I’d seen the basketball jersey one. The Gee’s Bend quilts are brilliant and fascinating, and have had a profound influence in quilting, especially the Modern Quilt movement. They’ve influenced my work directly, and I am so grateful to these fearless artists (and to you for talking about them.)

Thank you for the wonderful tour you gave our “second look” group. You’re inspirational.

Jane Friedman